Space4Youth: Young voices in the space sector

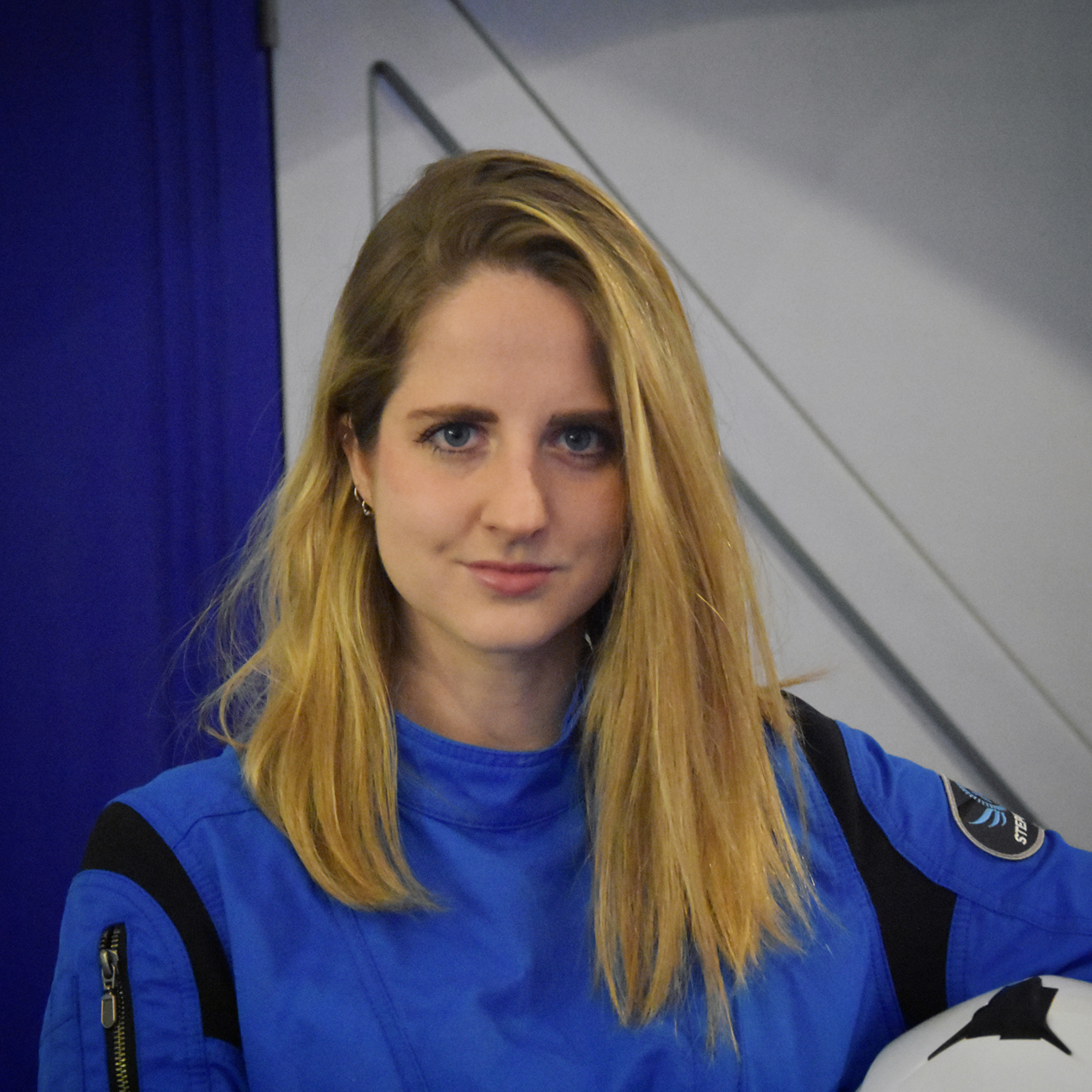

My two weeks as an analog astronaut in ESA's mission

by former UNOOSA intern Sabrina Kerber

Over the summer of 2019, I had the great experience of working as an intern at the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA), where I focused on communication and outreach activities. As a student of space architecture, in the process of writing my master thesis about lunar lander habitation, I was already deeply passionate about the space field.

The opportunities I had to meet actors from the space sector from all over the world and observe their work at the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) during this internship reinforced my desire to pursue a career in space exploration. Therefore, I was thrilled when, at the end of my internship, I was selected for the opportunity to be part of an analog astronaut mission organised by the European Space Agency (ESA).

Analog missions serve to test features of spaceflight missions and operations. This can include anything from robotics in emergency medical procedures to aspects of habitability and astronaut performance. Especially in human spaceflight, it is essential that all aspects of a mission are tested before launch, in order to identify and solve potential problems that could result in fatalities. Such simulations are often set in isolated, confined and extreme environments, to better recreate the harsh extra-terrestrial conditions, and involve crews of so-called analog astronauts. [1]

In order to leave the habitat, analog astronauts have to wear EVA spacesuits and carry life-support systems on their backs.

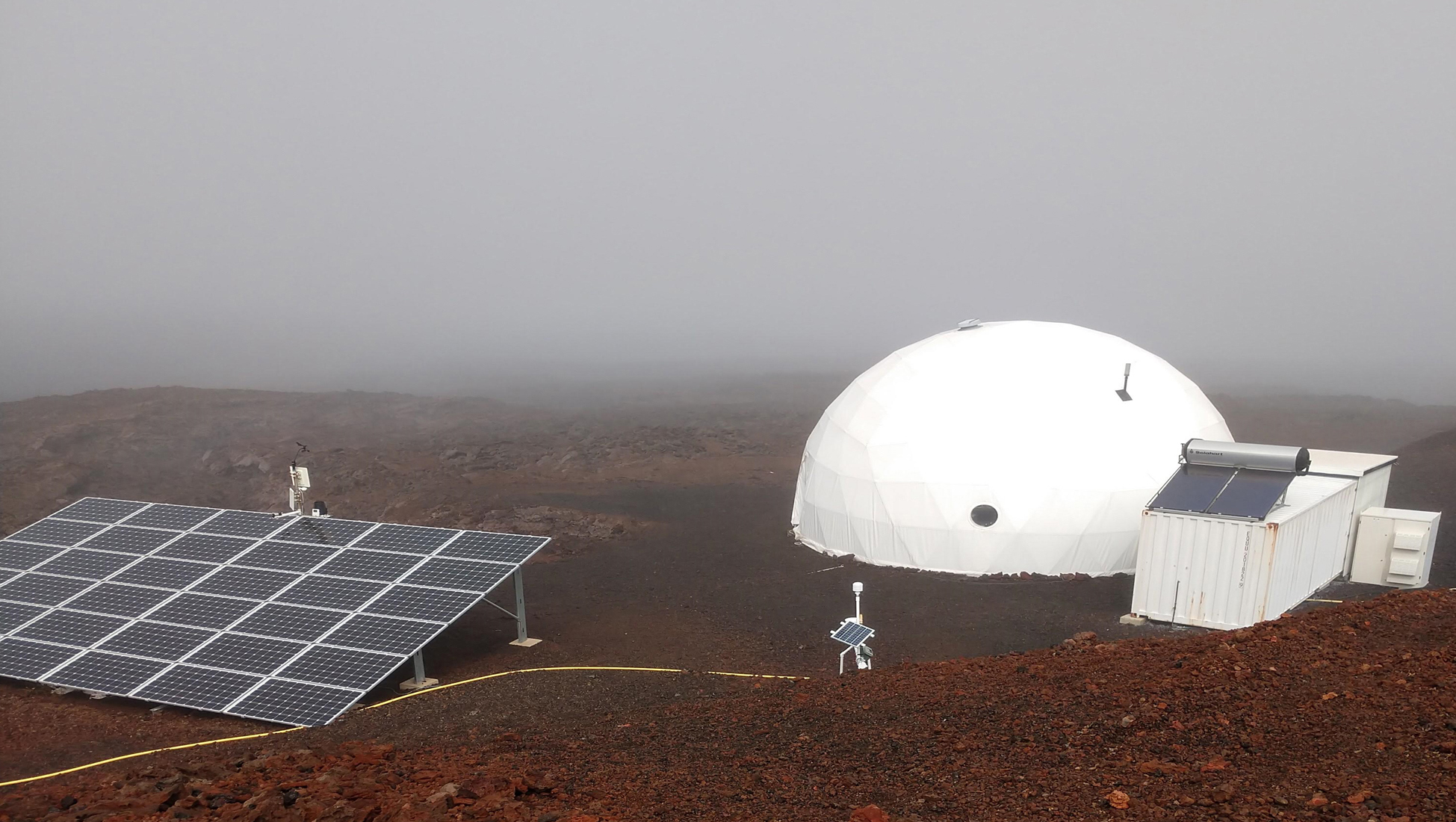

The mission I was asked to be part of, the EuroMoonMars International MoonBase Alliance HI-SEAS, or EMMIHS-II mission, was a collaboration between ESA's EuroMoonMars Initiative (EMM), the International Lunar Exploration Working Group (ILEWG) and the International MoonBase Alliance (IMA). It was set to take place at the Hawai'i Space Exploration Analog and Simulation (HI-SEAS), a renowned simulation habitat.

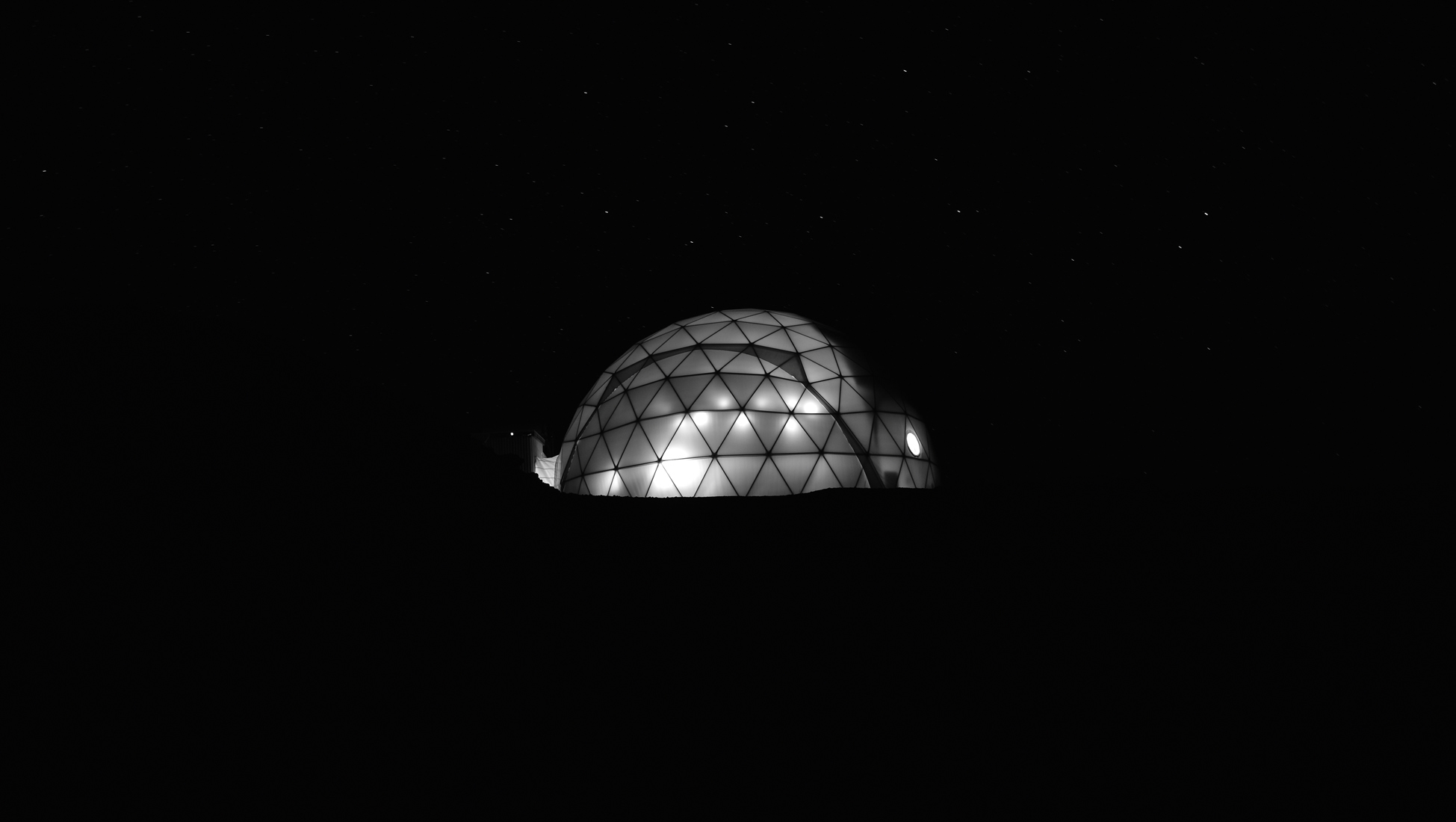

Set at 2,500 meters above sea level on the slopes of the Hawaiian volcano Mauna Loa, the HI-SEAS habitat offers room for crews of six analog astronauts. The barren landscape, high altitude and composition of the rock resemble that of the Martian terrain, thus providing excellent conditions for analog missions. Since 2015, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) have led several analog missions here, of up to 12 months. [2]

In February 2019, ESA joined NASA in facilitating astronaut simulations at HI-SEAS through their EMMIHS program, which includes missions both to 'Mars' and the 'Moon'. [3]

The dome-shaped habitat can only be entered through an airlock (left). Passing through the airlock requires 3 minutes of simulated de- or re-pressurization.

EMMIHS-II was to be a lunar simulation, with a focus on habitat architecture, robotics and space radiation. The simulation's duration was set for two weeks, as missions to the Moon will be much shorter than those to Mars. One lunar day lasts around two weeks on Earth: many upcoming Moon missions aim for this period of time, as it enables the use of daylight for solar energy.

To apply for this great opportunity, I travelled to ESA's ESTEC facility in the Netherlands, where I presented myself and my work on space architecture at several EMM workshops. However, working in space sciences wasn't the only criteria for being accepted. Analog astronauts also need to be physically and psychologically healthy, and the various team members have to be able to live and work together well. At the end of the process, I was selected by ILEWG and EMM to act both as Crew Engineer and Habitability Officer.

Our international EMMIHS-II crew also included another former UNOOSA intern: Brazilian aerospace engineer Ana Paula de Castro Paula Nunes, who had worked in the Office's Space Applications Section, joined as EMMIHS-II Chief of Engineering. For both myself and Ana Paula, this was an invaluable opportunity to extend our knowledge of space exploration, after having learnt about its policy aspects during our time at UNOOSA.

Our fellow crew members were our Commander, Slovakian astrobiologist Dr. Michaela Musilova, Chief Scientist and space radiation expert Charlotte Pouwels from the Netherlands, Chief Medical Officer Dr. Joseph D'Angelo from the United States of America and architect and Crew Engineer Ariane Wanske from Germany.

We spent several months in intensive preparation before the actual mission. This included crew training at ESTEC, where we learned to use various instrumentations but also got to enjoy lectures from experienced analog astronauts and ESA space experts, as well as working out almost daily to prepare ourselves for the exhausting Extra Vehicular Activities (EVAs) and the high altitude. We also had to prepare our personal projects, find collaborators and do a lot of fundraising, as parts of the mission costs had to be covered by us. These organisational tasks were an essential part of the mission and helped us a great deal in understanding the necessary foundations of any space mission.

The EVA helmets and backpacks containing the life support systems had to be charged and maintained by the crew engineers after every EVA.

Finally, at the beginning of December, our diverse international crew was ready to launch to the simulated Moon and take on the challenge as analog astronauts. These challenges include eating only food made from freeze dried ingredients, leaving the habitat only on approved EVAs while wearing spacesuits with integrated life support systems, and being restricted to eight minutes of shower time per week - all while conducting scientific experiments and working on personal projects.

One of the most important reasons to do analog missions is to see how astronauts adjust to unexpected situations. EMMIHS-II was hit with an unplanned obstacle right on the second mission day, when we woke up to find that our water levels were rapidly decreasing - something in the water-supply system was faulty. As on the Moon one cannot simply call for help or instantly get a water resupply, it was up to us to get to the bottom of the issue and solve it. While problems like this are often simulated on an analog mission, in order to create a more challenging experience, this wasn't the case here. The problem we were facing was real. With dangerously low water levels, Commander Musilova initiated the emergency protocol. For us, this meant a further restriction of our already very limited access to water, including not taking any showers until the situation was under control. Even though this was not a pleasant turn of events - especially as we were still obliged to work out at least one hour per day to keep up our muscle mass - it was a valuable experience to see how the crew adapted to the situation.

Going on an EVA meant crossing rough terrain to collect geological samples or explore lava tube systems.

After several engineering EVAs, we managed to fix the problem on Day 5 and were able to refocus completely on our scientific work. This included experiments on crew mood and effectiveness through adjusting the colour and privacy situation, investigating the effects of additive manufacturing on the human factors of extra-terrestrial missions, building a rover that could be controlled remotely from an ESA facility and growing plants in simulated extra-terrestrial soil.

One of the most rewarding experiences of EMMIHS-II was seeing how well we worked together as a team and how collaboration helped us expand our knowledge in space sciences and other fields. During a CASEVAC - a simulated medical emergency, in which our Commander took on the role of an accident victim during an EVA - Chief Medical Officer D'Angelo trained us on emergency procedures. Together we managed to carry the Commander and all the heavy life support from the site of the accident up the steep slopes to the habitat and 'save her life'. Even though those were probably the most exhausting moments during the mission, we didn't 'break simulation' but pushed each other to make it to the top. In moments like that, when we had achieved something that we previously thought impossible, or learned something that we had had no training on in advance, I felt most proud to be part of the mission.

The most important concept on EVAs is the so-called 'buddy system': no one is to be left alone. A built-in communication system in the helmets enabled us to always be connected.

While we were working hard inside the HI-SEAS habitat, a team of professionals from all over the world supported us from the outside. No space mission - whether simulated or real - can succeed without dedicated remote support. As part of our daily routine, we sent Science Reports to our CAPCOM at the Blue Planet Mission Control Centre, who advised us on technical issues and approved requests for EVAs after checking the atmospheric conditions of our environment. A second CAPCOM team at ESTEC provided daily project-based support and worked together with an additional remote support team of dieticians, biology experts and science communicators. While we were effectively cut out from everyone but our fellow crew members during the mission, this international team back on 'Earth' was essential to support us. [4], [5]

One of the most important takeaways from EMMIHS-II was learning new things about other space professions. We spent many evenings presenting to each other about our respective fields of expertise, the culture of our home countries and our ambitions for a career in space science. I gained a much better overview of the many disciplines involved in the space sector and helpful insights on how to pursue a career in the industry.

Lava tubes, which are accessed through so-called skylights, could be prime locations for lunar habitation. Investigating the spatial configurations and geological foundation of these caves gives important insights for future habitat designs.

But in the end it was all worth it and I can highly recommend the experience to other young professionals. It's an amazing opportunity to expand your expertise and further develop your projects Living as an astronaut for two weeks opened my eyes to the many operational needs of space exploration and strengthened my conviction that an extra-terrestrial mission is an extremely complex feat that can only succeed through teamwork.

[1] Reagan, M. L., Janoiko, B. A. et al. (2012). Analog Missions: Driving Exploration Through Innovative Testing.

[2] Caldwell, B.J., Binsted, K. (2016). Team Cohesion, Performance, and Biopsychosocial Adaptation Research at the Hawai'i Space Exploration Analog and Simulation (HI‐SEAS)

[3] Musilova, M., Rogers, H., Foing, B.H. et al (2019). EMM IMA HI-SEAS campaign February 2019. EPSC-DPS2019-1152.

[4] EuroMoonMars Instruments, Research, Field Campaigns and Activities 2017-2019.Foing, B.H., EuroMoonMars 2018-2019 Team. 2019 LPI Contrib. No. 3090.

[5] EMMIHS-II sponsors. Ruag Space, Agência Espacial Brasileira (AEB), Kurtz Ersa, db-matik AG, Tridonic GmbH, Capable BV.